Out of the Armchair – Part Two

High-five

I woke up the next morning stiff and cold. My phone, which became useless the moment I arrived, had plunged to 60% battery life.

As we gathered around the kitchen area, waiting for the water to heat up for coffee, we were given the choice of prospecting or working in the quarry for the day. I elected to go with the prospecting team.

We were each given a small field kit, which included: a Rite in the Rain All-weather Universal Field Notebook, a Eurex Garmin GPS, a Midland X-tra Talk walkie-talkie, 5% Vinac B-15 in acetone, a paint brush, a screwdriver, and a rock pick. The moment I picked up the rock pick, everything changed. Suddenly, the fantasy was real. I wielded that thing like I meant business. I wielded it like I was a danger to myself and others.

The moment it all changed

We jumped in the truck and drove off to a series of canyons to prospect for new fossil sites. As the week progressed, I began to recognize the amazing stratigraphy of the region.

At the very top was the Navajo Sandstone. This formation sometimes looks like a stately and wind-polished white capital dome sitting atop the rest of the layers. Beneath it is the reddish Kayenta formation, squat and compressed. Beneath that is the imposing Windgate Formation. Like giant blocky pillars, they give the canyons a temple-like appearance. This starkly vertical layer of scorched red sandstone documents a period in the Jurassic when a massive desert consumed the area. Because of this, few fossils are found from it. It was of little interest to us, but it was quite popular with rock climbers.

“I’m gonna gorilla-fist that crack.”

Below the Windgate was the focus of our expedition, the finicky but alluring Chinle Formation. This colorful band of rocks records the world of the Late Triassic, around 208 to 245 million years ago. These bands ranged from ruddy brown, to dull purple, to mint green in coloration. As the unfortunate downstair neighbor of the Windgate, the Chinle always ends up partially buried in eroded material. As we drove down the highway, we looked for small outcroppings where pristine Chinle was poking through.

Unlike the arid landscape that exists today, this area had lush swamps and waterways during the Triassic. A little-known group of Archosaurs made their first appearance in the Triassic: Dinosaurs. At the onset, they were not large, nor frightening, nor terribly prevalent on the scene. Like some gawky child actor stepping onto the stage for the first time, nobody could have guessed that these fairly minor characters would one day come in dominate the Mesozoic world.

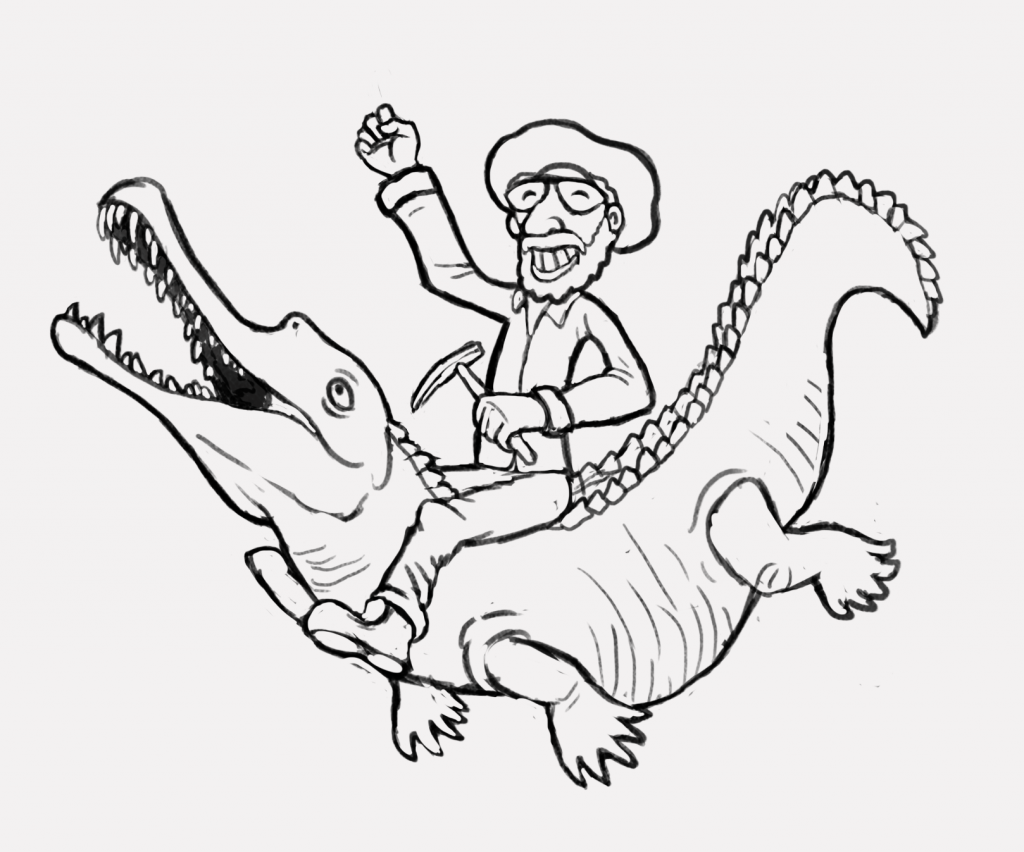

This world was instead ruled by other strange reptilian creatures. Cruising the waters were fearsome Phytosaurs, superficially crocodile-like creatures with long toothy snouts.

If you were to meet a Phytosaur and tell it that crocodilians would one day take its place, I bet it would say, “Well, I was into the whole aquatic-ambush-predator-niche before it was cool.”

Like all great scientific names, the name Phytosaur was a mistake. It means “Plant-lizard”, because when it was initially discovered there were rounded shapes that were interpreted as blunt plant crushing teeth. It happens. The area around us had produced Phytosaur teeth, squamosals, even a full skull.

“I’m putting out a bounty for an Aetosaur,” announced Tylor through the walkie-talkie.

Contemporary to the Phytosaurs were the Aetosaurs. These were a group of armored reptiles with pig-like snouts. They had been found in other Triassic locations, but for some reason, we had yet to find any good material at Indian Creek.

With our assignment, I made my way up the canyon walls. I followed Tylor for a bit before wandering off on my own. The canyon walls were steep. Everything was a little precarious. Every rock, even the large ones, moved a little when you rested your weight upon them.

I have heard that there is an art to finding fossils. I definitely don’t have it yet. The act is not simply about scanning the ground for something interesting, because every goddamn thing is interesting. Every rock is begging for your attention. Every stone is screaming to you, “I kinda look like a fossil.” I spent most of my time learning to block out all these impostors.

Besides its visual properties, there are other ways to determine if a fragment is potentially a fossil. We learned that due to the porous nature of bone, it will adhere to the tongue. I wonder what an onlooker would have thought of me casually picking up rock after rock, furtively licking each one.

Licking all the wrong rocks

I began to develop a pernicious internal narrative while prospecting, as if there was a film crew following me on the verge of a historic discovery. There was a building excitement that became deafening. It’s also what I imagine a gambling addiction is like. Maybe the next rock is the one. Maybe you are just moments away from hitting the jackpot. I had to force myself to silence these voices. I was just a guy walking among the rocks.

On my first day, I wasn’t having much luck, but Tylor came across something really neat. On a broad slab of rock was an isolated four-toed print, about the size of my own palm, and undeniably created by some ancient creature. I was amazed by how obvious it was right there out in the open. If the lighting was different it might have remained unnoticed. A fossilized bone is a great find, but a trace fossil like this captures something completely unique: movement and behavior. Some anonymous creature had taken a stroll across this surface, sunk its claws into the wet mud, and rested its weight against that limb. This was a record of that motion. This was a high-five (four) across time.

“Sorry to leave you hanging,” I thought.

For awhile, we stared agonizingly uphill.

“Where the hell did this thing come from?”

Paleontologists not only have to trace the ancient history of fossils but the more recent history as well. Where on the canyon did this thing come out of? Certainly it had eroded out from somewhere above us, as rocks rarely have the initiative to roll uphill. Where there is one track, there’s bound to be others. GPS coordinates were taken, and we left the site.

Around 6:00 P.M. we gathered back at camp. Those who had found things showed them off. I wasn’t disappointed that I had nothing to show. I was here for the experience. There was also a fully stocked beer cooler. Coming back to camp after a long day of hiking to crack open a Miller Highlife or an Allosaurus Amber Ale became one of the most refreshing parts of the day.

Every night we would gather by the campfire, soak in its warmth, dodge its spiteful plume of smoke, and make s’mores. Stories were told of the discovery of the first dinosaur in Utah Dystrophaeus, expeditions to Antarctica, creationist tour guides, our love for terrible movies, and more.

Before going to bed, I rotated my tent 90 degrees, thinking that a head-to-toe incline was favorable to a shoulder-to-shoulder one.

Wonderful improvisation

I spent the night perpetually slipping down into my sleeping bag. I dreamt that sleeping bags were inter-dimensional gateways to frightening worlds, and if you ever sink too deep into one you might not come back. I also woke up with melted marshmallow caught in my mustache.

We returned to the previous day’s canyon to extract the fossils we had found before: the footprint and a block of fish from an adjacent canyon. These fossils were too big to be carried back to the truck, so they needed to be sawed out with a rock-saw. Here I witnessed what I can only imagine is a sacred ritual for junior paleontologists.

“Elliot, today you become a man,” said Tylor, pulling out an empty frame backpack from the back of the truck.

The intern Elliot had elected, I think willingly, to carry the 35lb rock-saw up the canyon wall to the site.

I will note here, curious female names had been casually mentioned throughout the week. I don’t know when it hit me, but at one point I realized these were the names of various pieces of field equipment. Vanessa in particular was the rock saw. She looked like something you would strap to the side of your hotrod in the Mad Max universe.

Hiking behind poor Elliot, I was moved by his sacrifice and exertion, but I was also slightly worried that he would fall backward and decapitate me. I kept a safe distance as he scrambled up the hill.

We first hit the fish site. Even with GPS coordinates, finding the same site proved to be a challenge. We were like ants trying to navigate through a pile of loose legos.

“Fuck, we’re in the wrong canyon.”

After some backtracking, we got there.

Beneath an overhang was a large block of stone with several flattened fish. You could see every scale and fin ray. Around the main block, everyone was finding little pieces of fish. This was my chance. If I didn’t come back with something, I would hang up my paleontologist hat forever. I crawled down the wash and searched. I turned over sheets of rocks, I looked under overhangs, I combed the area as best I could.

There, right in front of me, was a small sheet of reddish rock with the dark imprint of fish scales. There was a head coming in from the left and the backend of another fish beneath it.

I showed it to Tylor, and he confirmed it was worth taking. He noted a small shape that could be an Ostracod, a small shell-encased arthropod, sitting against the fish’s snout.

“It’s obviously evidence of parasitism,” I suggested facetiously.

I was overjoyed. As I took GPS coordinates and recorded them to the specimen card, Tylor managed to turn the primary block of fish into a slightly more manageable block of fish. We then had a new problem: We had a rock saw and a brand new rock to return to the truck. Somehow not broken by the journey there, Elliot volunteered to carry the rock back while Tylor would take the saw.

Standing there on the side of a canyon, my left foot supporting my weight, my right hand clutching a sheet of rock, watching Elliot strap a 60-70lb block of stone to his back, I felt an odd tranquility. I saw the whole endeavor of paleontology for what it was, a wonderful improvisation.

“Don’t prolapse on me,” warned Tylor.

A few decades earlier, and I’m sure some of us would have been carrying dynamite sticks too.

We returned to camp and showed off our finds. That night I felt so pleased with myself that I did the dishes at night. I tucked myself into my sleeping bag feeling warm and accomplished. I closed my eyes, and luckily, I did not suffer the same affliction as the paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope, who used to have horrific nightmares about the creatures he discovered.

Returning to the Cenozoic

The week continued on. The prospecting team visited several other potential outcroppings. We drove down strange off-road trails where I was certain our truck would get stuck, but Tylor knew this vehicle well.

“Guys, we’re going rogue,” he warned as the truck lurched violently to the side, Danger Zone playing through the speakers.

After going out with the prospecting team all I week, I decided on my last day to go to the quarry. The quarry team was lead by Carrie, the Collections Manager at the museum and to my relief, a Wilderness First Responder. Getting to the quarry was a small adventure. We had to cross creeks several times, dodge cow patties, and crawl beneath a cattle fence. We passed an interesting outcropping of blue-grey marine limestone. It looked like pockmarked lunar rocks were emerging out of martian sand.

The quarry was in the Culter Formation. Here they were digging up the Permian, the period preceding the Triassic. From this quarry they were finding things like petrified trees, the toilet-bowl skulled Eryops, and Sphenacodon (picture a fin-less Dimetrodon. Dimetrodon Lite).

As I chiseled away some rock, Carrie silently agonized over a fossil she had covered in a plaster jacket. She had to turn it over to plaster the other side. The bone was fragile and inconveniently right up against a piece of petrified wood, resulting in a tricky situation known as a, “Flip and pray.” She pulled it off like a real pro.

Finally Sunday, our last day, arrived. The week’s exertions were beginning to make themselves known. I felt like someone had replaced my muscular system with a series of pulleys and yarn. Having not bathed in a week, I felt a thin layer of grime covering me. My finger prints were so dirty that my iPhone no longer recognized me.

Since this was our last breakfast, it was the simplest. We had instant oatmeal with dinosaur eggs. Each package had a joke:

“How much is a dimetrodon worth?”

“10 cents.”

We spend most of the day packing up the trucks. The last item to pack was the outdoor toilet.

“Chop chop Elliot, you still have the shitter to do.”

We got into the trucks and drove home. We stopped in Moab for lunch at the Moab Brewery. There, in the restroom, I saw myself in the mirror for the first time in recent memory. I looked pretty much as I had expected: Worn, but not worn through. Tired, but capable of more.

Driving home felt like returning to the Cenozoic. At one point, my phone buzzed to life with a bombardment of old notifications. I stared out the window as the terrain gradually changed. The wild red canyons became tamer and more muted. Strange towns like Salina, Gunnison, and Manti began to spring out of the earth, followed more familiar names like Provo, American Fork, and Sandy.

At several times in my life, I have faced a crossroads between the disparate worlds of art and science. In the last year at Disney, I was pretty confident I had taken a firm step into the world of art, perhaps a permanent step. But here I was, again peeking over the wall and fantasizing about what life would be like. I asked myself then, and indeed throughout the week, “Could I do this?”

Could I handle the physical exertion? The discomfort? The remoteness? Could I handle the constant disappointment? To that question in particular, part of me laid back and said, “Disappointment? Ha, you love of disappointment.”

We got back to the museum around 8 o’clock at night. The lights of Salt Lake City glittered below.

“Are you coming to the next dig?” asked Carrie.

“Yeah, sure.”

Late at night I arrived back at my one room apartment. I dropped my bag and boots near the door, hoping to sequester all my ambient dust to one region of the apartment.

I peeled off my clothes and stepped into the shower and never came out. I am still taking that shower.

The author triumphantly riding a Phytosaur

Sources

University of Utah: Chinle Formation

http://sed.utah.edu/Chinle.htm

National Park Service: Chinle Formation

https://www.nps.gov/cany/learn/nature/chinle.htm

Phytosaurs, (mostly) gharial-snouted reptiles of the Triassic, part I

Phytosauria, University of California Museum of Paleontology

http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/taxa/verts/archosaurs/phytosauria.php

Dawn of the Dinosaurs: The Late Triassic in the American Southwest (2015), by Christa Sadler, Dr. William Parker, Dr. Sidney Ash

My Beloved Brontosaurus: On the Road with Old Bones, New Science, and Our Favorite Dinosaurs (2014), by Brian Switek